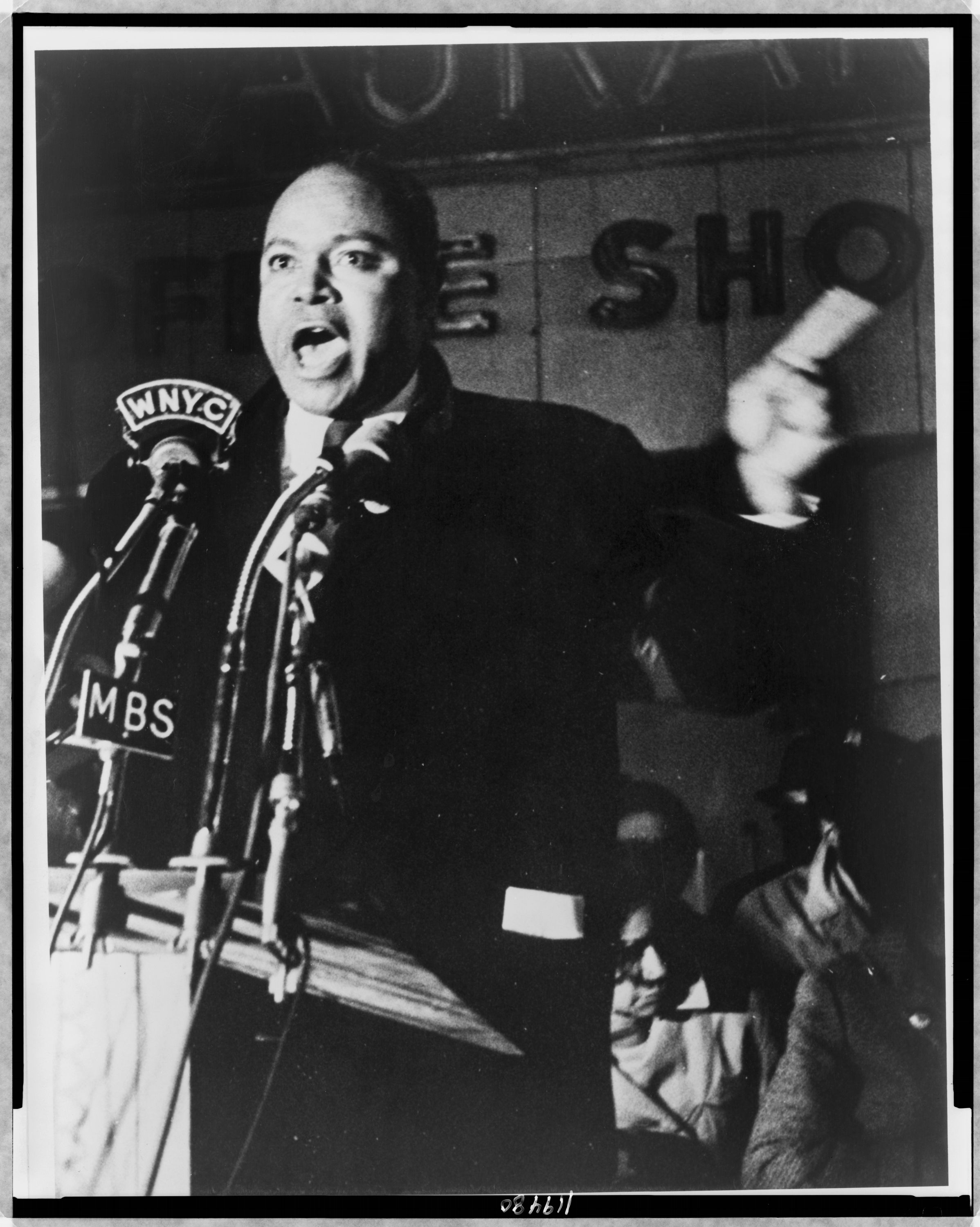

James Farmer, a principal founder of the Congress of Racial Equality and the last survivor of the "Big Four" who shaped the civil-rights struggle in the United States in the mid-1950's and 60's, died Friday, July 9, 1999 at Mary Washington Hospital, in Fredericksburg, Va., where he lived. He was 79. Farmer had been in failing health for years, losing his sight and both his legs to severe diabetes.

Farmer's main colleagues in the civil rights movement were the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, who was assassinated in 1968; Whitney Young of the Urban League, who died in 1971; and Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, who died in 1981.

Although attention in recent years has focused on Dr. King's activities, Farmer played a towering role in the movement as a direct-action leader of the organization popularly known as CORE. Claude Sitton, who covered the South for The New York Times during the civil rights struggle, observed: "CORE under Farmer often served as the razor's edge of the movement. It was to CORE that the four Greensboro, N.C., students turned after staging the first in the series of sit-ins that swept the South in 1960. It was CORE that forced the issue of desegregation in interstate transportation with the Freedom Rides of 1961. It was CORE's James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner -- a black and two whites -- who became the first fatalities of the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964." The three were murdered by a gang of Klansmen and buried beneath an earthen dam near the town of Philadelphia. The CORE workers were investigating a church burning and promoting black voter registration.

Farmer himself risked his life in several demonstrations. In 1963, Louisiana state troopers armed with guns, cattle prods and tear gas, hunted him door to door when he was trying to organize protests in the town of Plaquemine.

"I was meant to die that night," Farmer once said. "They were kicking open doors, beating up blacks in the streets, interrogating them with electric cattle prods." A funeral home director had Farmer "play dead" in the back of a hearse that carried him along back roads and out of town.

Farmer went to jail for "disturbing the peace" in Plaquemine, and was behind bars on Aug. 28, 1963, the day that Dr. King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech as the climax of the March on Washington. Farmer sent his own speech to the March on Washington, which was read by Floyd McKissick, an aide in CORE. "We will not stop," Farmer wrote, "until the dogs stop biting us in the South and the rats stop biting us in the North."

At one point, a friendly F.B.I. agent told Farmer that an informant had infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan in Louisiana, and had reported that the Klan had voted to kill Farmer the next time he set foot in Bogalusa. "Tell me," Farmer said to the agent, "were there any dissenting votes?"

Farmer was a disciple of Mohandas Gandhi, and it was Gandhi's strategy of nonviolent direct action that was to become Farmer's weapon against discrimination. A fierce integrationist, he enlisted both whites and blacks as CORE volunteers. Some white liberals who generally approved of what Farmer was doing frequently advised him to be more patient with a recalcitrant society dominated by whites. They thought that the doctrine of nonviolence was radical in its use of picketing and sit-ins. Some thought it engendered bellicose responses from whites that did nothing to further amicable race relations.

On one tense occasion in the early 1960's, after a particularly vicious spate of violence, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy suggested that Farmer's followers postpone some of their "freedom rides" -- designed to desegregate the interstate bus system in the South -- so that everyone could "cool off." Farmer refused, saying, "We have been cooling off for 350 years."

As the turbulent decade of the 1960's unfolded, some blacks who despaired that they would ever have an amicable relationship with the white majority and regarded nonviolence as more of a weakness than a strength, on occasion would ask Farmer, "When are you going to fight back?" Farmer would always reply, "We are fighting back, we're only using new weapons."

"I lived in two worlds," Farmer said late in life, recalling his role in the movement. "One was the volatile and explosive one of the new black Jacobins and the other was the sophisticated and genteel one of the white and black liberal establishment. As a bridge, I was called on by each side for help in contacting the other."

James Farmer, the son of a minister and the grandson of a slave, came to feel that his generation of leaders had been all but forgotten in recent years, with the exception of Dr. King because of television's use of film clips replaying his "I Have a Dream Speech."

James Farmer, the son of a minister and the grandson of a slave, came to feel that his generation of leaders had been all but forgotten in recent years, with the exception of Dr. King because of television's use of film clips replaying his "I Have a Dream Speech."

Farmer was appalled to learn that in one survey of blacks taken in the 1990's, somebody said he thought that Dr. King's claim to fame was that he had "worked for Al Sharpton" and that many young blacks had never heard of Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young and Farmer or had only the vaguest notion of what they had stood for. And so when President Clinton awarded him a Presidential Medal of Freedom in January,1998, Farmer said he felt "vindication, an acknowledgment at long last."

Farmer was proud of his role in founding CORE and guiding it to becoming one of the most effective civil rights organizations of the 1960's. The motivation for CORE came on a bright spring afternoon in Chicago in 1942 when Farmer, then just a year out of theology school, was walking with a white friend, George Houser. The two decided to stop for coffee and doughnuts in Jack Spratt's Coffee Shop on the South Side.

The counterman made them wait even though there was almost nobody in the restaurant, then tried to charge them a dollar apiece for doughnuts that were going for a nickel. Finally he ordered them out and threw their money on the floor.

"We felt he had a problem about race," Farmer said later, recalling the incident with typical understatement. Farmer, Houser and a few others staged a successful sit-in demonstration at Jack Spratt's. It was the first direct action of an organization they formed, called at the time the Committee on Racial Equality.

"We felt he had a problem about race," Farmer said later, recalling the incident with typical understatement. Farmer, Houser and a few others staged a successful sit-in demonstration at Jack Spratt's. It was the first direct action of an organization they formed, called at the time the Committee on Racial Equality.

Within a year, CORE had a national membership, and within a few years a roster of more than 60,000 members in more than 70 chapters, coast to coast. In its heyday in the 1960's, it claimed a membership of 82,000 in 114 local groups.

Farmer was equally proud of the work he did in 1961, when he organized the Freedom Rides in the Deep South, a perilous effort in which any black and white supporters were attacked and injured by white segregationists.

James Leonard Farmer was born on Jan. 20, 1920, in Marshall, Tex. His father was James Leonard Farmer Sr., the son of a slave, a minister-scholar who became a college professor and who delighted in teaching literature in Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic. He was believed to be the first black man from Texas ever to earn a doctorate, which he did at Boston University. Farmer's mother was the former Pearl Marion Houston, a teacher.

As a boy, Farmer was shielded from the worst aspects of racism. He used to say that as a "faculty brat" he spent most of his time on the campuses of black colleges in the South where racial incidents would not ordinarily happen. The houses he lived in were filled with books and the conversation frequently was about the ideas in those books, most of them about ancient cultures. They did not ordinarily speak of the bleak, segregated world that existed outside the campus.

Farmer told Gay Talese of The New York Times in 1961 that his first awareness of race came when he was 3 or 4 years old, living in Holly Springs, Miss., where his father was on the faculty of Rust College. One very hot day, young James went shopping with his mother and asked her to buy him a soft drink. His mother told him he would have to wait until they got home. He saw a white child go into a drug store, and it was not until he got home that his mother explained to him why he could not do the same thing.

"Until then, I had not realized that I was colored," Farmer said. "I had lived a sheltered life on campus. My mother fell across the bed and cried." Farmer said it did not make him bitter, but, over the years, he became "determined to do something about it."

His determination was strengthened between 1934 and 1938, when he was an undergraduate at Wiley College in Marshall, Tex. He would go to movies in Marshall, and was made to sit in the "buzzard's roost," the balcony set aside for black people. During the same period, he got a job as a caddy, but found himself segregated even in the caddy yard.

Years later, when he looked back at his youth in the South, he sometimes remembered the times when black children and white children played peacefully together. The real separation between the races came at puberty, he recalled, when white parents reinforced in their children that they were white and that blacks were something else. He recalled that when he was in his teens, the friends he had known as a little boy "would only look away" when they saw him in the street.

Farmer considered both medicine and the ministry as vocations during his undergraduate days. He discovered that he could not stand the sight of blood and so in 1938, after he completed his baccalaureate work at Wiley, he enrolled in Howard University's School of Religion. It was at Howard that he was introduced to the philosophy of Gandhi.

With his commanding frame, booming bass-baritone voice and decisive way of speaking, everyone thought he would be a fine preacher. But to the dismay of his father, Farmer decided against becoming a Methodist minister because, in those days, the Methodist church in the South was segregated. "I didn't see how I could honestly preach the Gospel of Christ in a church that practiced discrimination," he said. He was quick to assure his father that his turning away from Methodism did not represent any lessening of his belief in Jesus.

After World War II started, Farmer, a conscientious objector, served as race relations secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a pacifist organization. He subsequently also worked as an organizer in the South for the Upholsterer's International Union and later for the State, County and Municipal Employees Union.

In the late 1940's, before giving CORE his full attention, he was also a program director for the N.A.A.C.P. and wrote radio and television scripts as well as magazine articles on race relations for Crisis, Fellowship, World Frontier and the Hadassah News.

During the 1950's, he worked assiduously to bring an end to segregation in Southern schools. He planned and organized CORE projects, including a Pilgrimage of Prayer in 1959 to protest the closing of public schools in Richmond, Va., to avoid complying with the 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in the public schools.

Throughout the 1960's, CORE's black volunteers, under Farmer's personal direction, stood peacefully in lines all over the South, insisting on the right to enter theaters, coffee shops, swimming pools, bowling alleys and other segregated public places from which they had always been barred.

Farmer did not become the $11,500-a-year salaried national director of CORE until February 1961, just before he initiated his first Freedom Ride. His father, by then retired and living in Washington, died just as Farmer was getting this effort started.

CORE and another civil rights group, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, held a Freedom Ride in 1947. A year earlier, the United States Supreme Court had ruled that segregated seating of interstate bus passengers was unconstitutional, but the ruling was virtually ignored in the South. An integrated group was sent to call attention to that injustice.Some were arrested and served on a chain gang in North Carolina.

In 1961, CORE decided to try again. Its bus riders were assaulted when using restrooms and lunchrooms in terminals in Virginia and the Carolinas.

In Alabama, their bus was firebombed in the town of Anniston and the riders stoned. In Birmingham, a mob attacked the riders and one of them, William Barbee, was paralyzed for life. They were savagely beaten again in Montgomery.

Everyone expected more violence when a small band of young blacks and whites from CORE and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee boarded buses for the last leg of the Freedom Ride, from Montgomery to Jackson, Miss. Dr. King, on probation for his arrest during sit-ins in Atlanta, decided not to go and was criticized for his decision. When a follower asked Farmer if he was going, Farmer climbed aboard the bus though quaking with fear. But the journey was completed without further violence because of a deal worked out between Attorney General Kennedy and James O. Eastland, the segregationist Senator from Mississippi. But Farmer was arrested in Jackson for disturbing the peace and spent 40 days in Mississippi jails.

If the Freedom Rides stiffened opposition to desegregation in some quarters in the South, the courage of Farmer's CORE volunteers captured the imagination of blacks throughout the country, who decided to join the civil rights struggle. It also aroused the conscience of many whites both in America and abroad.

"In the end, it was a success," Farmer said of the Freedom Rides, "because Bobby Kennedy had the Interstate Commerce Commission issue an order, with teeth in it, that he could enforce, banning segregation in interstate travel. That was my proudest achievement."

Subsequently, Farmer turned his attention to the lack of employment opportunities for blacks. He sought no quotas because he said he was convinced that if blacks were giving an fair chance they would do just fine, but he made it clear that he wanted to see some black faces at construction sites, especially those financed with public money. He ordered sit-ins in the early 1960's at the New York offices of Mayor Robert F. Wagner and Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller. He also organized picketing at White Castle hamburger stands in New York City, accusing the chain of refusing to hire black workers. "We are not pressing toward the brink of violence, but for the peak of freedom," he said.

Subsequently, Farmer turned his attention to the lack of employment opportunities for blacks. He sought no quotas because he said he was convinced that if blacks were giving an fair chance they would do just fine, but he made it clear that he wanted to see some black faces at construction sites, especially those financed with public money. He ordered sit-ins in the early 1960's at the New York offices of Mayor Robert F. Wagner and Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller. He also organized picketing at White Castle hamburger stands in New York City, accusing the chain of refusing to hire black workers. "We are not pressing toward the brink of violence, but for the peak of freedom," he said.

Farmer kept CORE focused on integration. When, in 1965, CORE officials called for a pullout of American troops from Vietnam, Farmer insisted that the organization reverse itself. He did not approve of the war, but thought that CORE should not express itself on American foreign policy.

He resigned his CORE director's job the same year to head what he hoped would be an intensive literacy project financed by the Administration of Lyndon B. Johnson. The project failed to materialize, and there was an open break between Farmer and R. Sargent Shriver, the director of the Federal antipoverty agency, the Office of Economic Opportunity.

Farmer did several things in the late 1960's. He taught at Lincoln University, a black institution in Oxford, Pa., about 45 miles southwest of Philadelphia, advised the State of New Jersey on problems of illiteracy, and, in 1968, ran for Congress. A Liberal candidate, backed by Republicans, in Brooklyn's 12th Congressional District, he lost to the Democrat, Shirley Chisholm. Also in 1968, he supported the re-election of Senator Jacob K. Javits, a liberal Republican, who was jeered at a campaign rally in Bedford-Stuyvesant. "Jake Javits may be white on the outside but he's black on the inside," Farmer said, calming the crowd. That same year he backed Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey in his run for the Presidency.

It had always been Farmer's position that blacks, no matter how they felt, should be a part of government, and so he readily accepted an invitation from President Richard M. Nixon in 1969 to become an Assistant Secretary in the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Farmer was immediately attacked by some militant civil rights advocates, who wanted nothing to do with Nixon. But Roger Wilkins and Whitney Young refrained from criticizing Farmer because they agreed with him that blacks needed such involvement if they were ever to have anything to say about shaping national policy on race.

At first, Farmer defended Nixon's racial policies, but in 1970 he quit his post complaining that the Washington bureaucracy moved too slowly and saying that he felt he was more effective outside it. Somewhat later, he complained that Nixon had virtually no contact with blacks and instead relied on Leonard Garment, a white aide, to explain black problems to him.

In 1975, Farmer broke with CORE over what he regarded as CORE's excessively pro-leftist position that sided with the Marxist faction in the civil war in Angola. He resigned from the group he had founded the next year. In 1978, he lent his name to a lawsuit that attempted to unseat CORE's director, Roy Innis.

In the mid-1980's, Farmer worked hard on his memoir, "Lay Bare the Heart," which was published in 1985. Claude Sitton, reviewing the book approvingly for The New York Times, said that Farmer, "more than any other civil rights leader, fought against (racism) and attempted to hold the movement true to its purpose."

Among Farmer's other writings was "Freedom -- When?" a book published in 1966. Before his health failed he taught for several years at Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg.

Farmer's brief first marriage ended in divorce. He married Lula A. Peterson, whom he met in 1949 when she was a graduate student in economics at Northwestern University and a white member of the CORE chapter in Evanston, Ill. She died in 1977. They had two daughters, Tami and Abbey.

In his last years, Farmer lived alone in a remote house near Fredericksburg, confined to a wheelchair and often in need of an oxygen tent. When visitors came, he would joke about the times he had come close to death. Asked by a friend if he had ever seen a tunnel. Farmer acknowledged that he had, but instead of seeing St. Peter at the end of it, he saw the Devil. "And he said, 'Oh, my God, don't let this nigger in! He'll organize a resistance movement and try to put out my fire.'